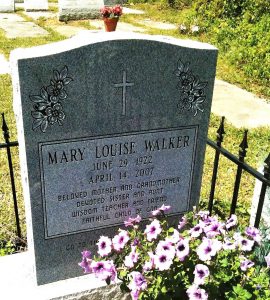

Is there a woman anywhere who hasn’t heard: “the older you get, the more you become like your mother”? Typically, these words are intended as a warning or an indictment, not a compliment. How then do we explain that annual rite of spring, committed to exorbitant displays of devotion and no small investment of dollars to honor mothers? Perhaps it was recognition of this discrepancy that accounted for my mother’s refusal to wax sentimental about Mother’s Day. She pointedly ignored even the simplest of rituals: wear a red rose if your mother is alive, a white rose if she is not. It wasn’t that she didn’t love her mother, nor was it unhappiness with being a mother. In fact, always one for a memorable rhyme (meaning she often required me to memorize them), one of her favorites began with “I love you, Mother, said little John”. As you might guess, a lineup of siblings march through the verses to declare their devotion to “Mother” before merrily skipping off to enjoy their day. It was only “little Fan” who decided to express her devotion by “helping in any way I can”. Now my clinical brain (and I’m guessing the brains of my many colleagues and friends) might think perhaps little Fan was overly responsible, enmeshed, parentified, yada, yada, yada. The larger point, however, is this: love is what we do – as persons, as families, as a culture. My mother knew and lived that truth. Were she alive, she would be 96 years old this month. In this season of the year and in this season of my life, it is to her wisdom that I turn to guide me as I traverse this cultural chasm between what we say and what we do.

All too often what we say about mother-love and family values is “Hallmarked” or sentimentalized. Roses, frothy greeting cards, and syrupy tweets notwithstanding, sentimentality serves a political function. As Gertrud Mueller put it: “Sentimentality is what we feel when we scoop out part of the truth – then slather like syrup over what we don’t want to see.” To put it bluntly, sentimentality obscures the hard truths lived by mothers and families in a culture riven by racial, economic, and gender disparities. These disparities create a fault line between the deserving and undeserving, the commendable and the contemptible. They create “cast-off” mothers and families, whose exclusion from the resources and opportunities is justified as necessary for the security and well-being of the “deserving” mothers and families. The valiant striving of the undeserving is rendered invisible; their inevitable suffering is attributed to their innate unworthiness.

The sentimentalized narratives of American family life normalize the fault line; they make the inequities hard to notice and name. The sugar-coated blaming makes inequity not only all right, but right. This kind of saccharine sentimentality harms families on both sides of the fault line. The wounding experienced by those who fall on the deserving side of the fault may be less obvious, but the suffering is no less real. They are the ones who are more likely to be bamboozled by myths of meritocracy. The narratives also come with a set of images and instructions about the normal American family, starting with two cisgender, heterosexual parents who do the right things to produce bumper-sticker-worthy offspring. Because the sentimentalized narratives serve up the “undeserving” scapegoats, they often never see the true sources of their misery. Therefore, their economic struggles can be blamed on some undeserving person who got their promotion, or some undeserving child whose affirmative action seat took away their child’s educational opportunity.

The marketing of sentimentality obscures the link between their frustrations and the systems of governance and hyper-capitalism that are specifically designed to perpetuate the “entitlements” of the ruling class. Coupled with the myth of meritocracy, the illusion of the self-sufficient, self-contained nuclear family is a set-up for failure and profound shame. It results in a constricted imagination of family that weakens the quality of connection within families. Emotional fragilities may go unnoticed or be kept hidden from view. The individualistic ethos of the “right to privacy” easily morphs into pathological isolation within the family. What gets called family values might more accurately be described as spiritual sterility; they are often little more than attempts to codify the fault line between deserving and undeserving. Scrambling to stay above the fault line results in deep denial of vulnerabilities that need tending. Therefore, when suffering breaches the boundaries intended to protect the “deserving” from ills that plague “undeserving” families, denial then morphs into bewildered disbelief: “how could this happen here – to people like us”. So, here we need to face: sentimentalized narratives about mother-love and family values function to distance us from our truths, thus making all families susceptible to the ravages of culturally constructed disconnection. My mother would have none of it.

My mother lived a contradiction; she was the center of my life and I the center of hers. Yet that reality was contradicted by her assigned place in the larger world. I was in my twenties with a daughter of my own before I spent a full day with her on Christmas. Don’t get me wrong. Christmas in our family was ever joyous. I can still remember the joy in her eyes watching my excitement as I turned from precious gift to precious gift. Then she would march me off to my great-grandmother where I would spend the day with my beautiful brown dolls, stacks of coloring books, and the occasional chemistry set. There I would await her early evening return from the family whose needs for comfort, convenience, and togetherness somehow invalidated our own. She was a black (colored) maid for a Southern white family. Their claims on her time, her attention, and her wizardry in the kitchen superseded any need we might have to spend that most happy of holy days together. I tell this not as a mournful plaint, but as a totally unexceptional fact of our lives. Indeed, this fact is unexceptional because it is completely aligned with American history. Families who somehow (e.g. race, class, gender) fall on the “un” side of the deservingness fault line have been systemically marginalized, destroyed, broken – then blamed for their brokenness.

In describing what he called the “second Middle Passage”, historian Ira Berlin recounted the devastating grief of slave mothers who watched their children being sold to different masters, or worse, “sold down the river” to satisfy the demands for free labor as the country grew westward. Slave mothers and fathers who dared to cry or complain when their children were ripped from them were brutally punished. According to Thomas Jefferson, this cruelty of separating families from each other was justified (in fact, it wasn’t even thought to be cruelty) because slaves were “incapable of expressing sentiment or love”. Yes. That Thomas Jefferson. Of course, the devastation was not limited to African American families. Under the guise of “for their own good”, Native American children were forcibly removed from their parents to attend assimilationist boarding schools. As one school founder put it, the goal was “to kill the Indian in him and save the man”. Although 20th-century legislation formally prohibited the abduction of Native children, vestiges of these practices and most certainly the sequelae of intergenerational trauma remain to this day.

Now in this 21st century nation, a new class of undeserving families are suffering the brutality of forced separation, abduction, and for all we know, annihilation when they try to cross the southern borders. Boston Globe columnist Liz Goodwin calls it the “new trail of tears”. Like the 3rd American president, the 45th POTUS justifies this government-mandated violence by criminalizing the children and their parents. And if their criminality is not convincing enough evidence of their undeserving-ness, he moves on to dehumanizing them: they’re “animals”. He describes the presence of immigrant families as an “infestation” as if they are vermin or termites determined to eat away at the foundations of American society. The 45th POTUS doesn’t seem to have as many words at his disposal as his 19th-century predecessor, but he puts the few he has to stunningly pernicious use: “They (meaning the children) look innocent, but they’re not”. The truth, of course, is he doesn’t need words when can deploy his minions to execute his hatreds as government policy. Reductions to the already paltry provisions made for families receiving food and nutrition assistance is but one heartbreaking example. But hey – to paraphrase a comment by economist Paul Krugman, “whose fault is it when children are irresponsible enough to be born to poor (and often times politically persecuted) parents?” Besides, “these aren’t our kids”.

With a Little Help from Mother-wit

As a child and throughout her adult life, my mother lived in a culture that was specifically designed to make her believe that she was undeserving. Her own father died when she was fifteen. Before then however, he was disabled in a railroad accident when she was eleven. Although federal law mandated school attendance until the completion of elementary school, she was never a “real” child in the cultural narrative of the time. At age eleven, she became his surrogate provider: she helped her mother support the family by joining her to take in washing, clean houses, and care for the children of white families who lived “on the hill”. As an adult, she had none of the accoutrements that might bestow validity on her as mother or personhood. She was black, poor, uneducated. Furthermore, she was a single mother, a social status fraught with suspicions of unworthiness. Fortunately for me, and I would say for many children and families in her sphere, she trusted herself to be the author of her own story, and that meant resisting the sentimentalized narratives promulgated by the racially-polarized, class-divided culture. The narrative that shaped our lives as family was guided by something called mother-wit. It’s actually not taught through books, but through relationships. Foundational to those relationships are three themes: Blessed Be the Ties; Make a Way Out of No Way; and We’ll Sit at the Welcome Table.

Blessed Be the Ties

Far be it from me to romanticize oppression of any kind; however, I do know through my mother’s example that life-empowering resistance skills can be cultivated on the “undeserving” side of the fault line. Writer bell hooks attributed it to the “oppositional gaze”, which opens access to alternative ways of knowing, interrogating, and naming reality. The women who raised me called it “mother-wit”. Mother-wit doesn’t come from books or biology, but from relationships powered by courage, compassion, and commitment to the indissoluble ties that bind us each to the other. The ties matter. My mom would say this: “You should raise your child in a way that makes other people like them.” In contemporary culture, that’s a cringe-worthy statement. It sounds a lot like requiring mindless obeisance. But here’s what she meant: simply put, it takes a village. She meant this not as some new-agey sentiment, but as a woman who knew that at no time in American history was there any presumption that black families had a right to stay together. Neither was there a presumption that black mothers had a right to available to and take care of their own children.

My mother was not entrapped in myths about the sanctity, self-sufficiency, or the presumptive superiority of the nuclear family; therefore, she recruited helpers. Sometimes they were people I didn’t know, like whoever it was who would tell her if I deviated from my prescribed route home from school and ended up say on Chestnut Street instead of Maple Street. Or sometimes it was someone I did know: like the kindly Miss Nell who owned a small store and doubled as a crossing guard during after school hours. If I didn’t show up during her duty hours, my mom asked her to “watch out for me” – as I sometimes stayed late for a play or choir rehearsal. This was not a monetized arrangement: this was deep acknowledgment between two women (who didn’t even socialize) that the collective safety and survival of black children depended upon their “watching out for each other”. I’m not saying we as children always enjoyed all of this attention and intervention. I’m pretty sure there were times when we would have preferred to go about our raucous play or “too quiet” play or various misadventures without the Miss Julia’s and Cousin Leah’s of the neighborhood interrupting us with “what are you children doing?” These women put the “know” in nosy neighbor, and I’m also pretty sure that their “knowsy-ness” saved lives. Under their boundary-crossing, watchful care, it was unlikely that concerns with family “privacy” could morph into pathological isolation. And I’m pretty sure none of us could have stockpiled weapons without one of them knowing. There was always a “Miss Julia” around to notice if something was amiss and to dutifully report it whenever a parent came back from wherever life took them during the work day or nighttime hours. The fact that the Miss Julia’s typically had no biological ties to any of the children mattered not at all. What mattered were the ties that bind – that affirmed our collective possibilities and our shared humanity.

Make a Way Out of No Way

I remember this scene very clearly. On a summer Saturday morning, my mother and I went window shopping after we walked into town to pay the rent. This is the exchange that unfolded as we stood in front of Rayless Discount store window.

My mother: “What do you think you want to be when you grow up?”

Me: A nurse. (I liked their stiff, white uniforms and those perky little caps.)

My mother: “You could be a doctor you know. Ladies can be doctors too.”

This she said as a matter-of-fact: as if broken desks in segregated schools, cast-off books, and her $3 dollar a day job had no impact on my future at all. I know she had never heard of Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, because she never told me about her. She just knew that the children of my generation were destined to live in a world larger than the one the Jim Crow culture prescribed for us. My cousin Peggy (aka Dr. Thurmond) has similar memories of her. Once on a different summer’s day when she was fresh out of first grade, she complained to my mother that she had nothing to do. My mother said: “Read. You don’t have to be in school to learn.” And that was trademark mother-wit: making a way out of no way – every day. In other words, she and other women like her knew that their job was to help us learn how to blaze trails, even if they didn’t know where those trails might lead. The poet Carolyn Rodgers put it most eloquently in her paean to “those women stout of arm, who knew what we must know without knowing a page of it themselves.” Making a way out of no way meant resisting the racist cultural narrative every day. It was more than just a slogan; it was a competency-driven, highly nuanced way of life. It meant, for example, living the distinction between offering service and practicing servility. My mother provided domestic service for a family for over fifty years, but she never once bought a “maid’s uniform”, nor would she wear one outside of her workplace. As she said to her employer: “I don’t need a maid’s uniform; you need me to wear one.” Once her work day was done, she would shed the employer-provided uniform and catch the bus home in her own clothes. Moreover, she had no fear of rubbing against the cultural grain, even if doing so meant risking disapproval from her elders. Although Southern culture (on both sides of racial divide) had strong linguistic traditions, she taught me that I never had to say “Ma’am” or “Sir” to anyone – white or black. For sure she expected me to be respectful of my elders, but that, she said, could be accomplished with “yes” and “no”, never (definitely never) “yeah” and “naw”.

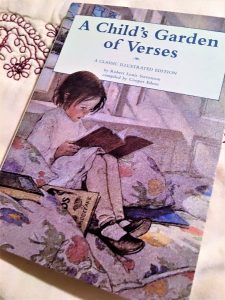

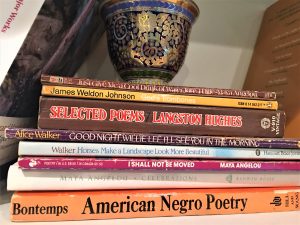

There was one other practice mandate: never be “common”. To be “common” was to live without dignity, to live within the soul-strangling boundaries of racist politics.  That was probably why she was reading to me and helping me memorize poems from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Child’s Garden of Verses before I could read myself. She didn’t want me to be misled by the fact that all of the illustrations featured fair-haired children. Poetry, she knew, belonged to brown-skinned children too. By the time I was nine, the antebellum antics portrayed in Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poetry were as familiar to me as the “spreading chestnut tree” in Longfellow’s poetry. As a pre-teen, I knew as much about Perry Como’s music as I did about James Brown’s – although my first childhood home was just a block away from his. (Of course, it was pretty cool that James Brown not Perry Como would drop by our old elementary school.) To be common was to walk out in public wearing un-pressed clothes and un-combed hair; to speak in unmodulated tones with subjects and verbs fighting against each other. In the words of my mother’s generation, to be common was to “act like you don’t have people” – people who matter to you and to whom you matter. That’s why the “Miss Julia’s” of the neighborhood wouldn’t hesitate at all to say, “Come here, Honey and let me fix that hem”. I can imagine that today such boundary crossing would seem almost felonious. Today her “uncommon” sensibilities might be denounced by some as respectability politics. Back then it was called “acting white”. But mother-wit is precisely what makes those denouncements ring hollow. Respectability politics consists “performing” to garner approbation from an otherwise disapproving audience. Mother-wit, in contrast, neither seeks approval nor cedes authority. My mother gave not one whit about gaining the approval of a system that stratified families into deserving and undeserving based on skin color, wealth or both: families who had no rights that deserving families were bound to respect. She would walk with me to the city auditorium to hear The Messiah because Handel was as much our legacy as was Howlin’ Wolf. She would not submit to a narrative that would deny us access to experiences that expand the imagination or lift the human spirit. By rejecting the false narratives of the dominant culture, she claimed the right and the responsibility to turn “no way” into pathways toward dignity and possibility.

That was probably why she was reading to me and helping me memorize poems from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Child’s Garden of Verses before I could read myself. She didn’t want me to be misled by the fact that all of the illustrations featured fair-haired children. Poetry, she knew, belonged to brown-skinned children too. By the time I was nine, the antebellum antics portrayed in Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poetry were as familiar to me as the “spreading chestnut tree” in Longfellow’s poetry. As a pre-teen, I knew as much about Perry Como’s music as I did about James Brown’s – although my first childhood home was just a block away from his. (Of course, it was pretty cool that James Brown not Perry Como would drop by our old elementary school.) To be common was to walk out in public wearing un-pressed clothes and un-combed hair; to speak in unmodulated tones with subjects and verbs fighting against each other. In the words of my mother’s generation, to be common was to “act like you don’t have people” – people who matter to you and to whom you matter. That’s why the “Miss Julia’s” of the neighborhood wouldn’t hesitate at all to say, “Come here, Honey and let me fix that hem”. I can imagine that today such boundary crossing would seem almost felonious. Today her “uncommon” sensibilities might be denounced by some as respectability politics. Back then it was called “acting white”. But mother-wit is precisely what makes those denouncements ring hollow. Respectability politics consists “performing” to garner approbation from an otherwise disapproving audience. Mother-wit, in contrast, neither seeks approval nor cedes authority. My mother gave not one whit about gaining the approval of a system that stratified families into deserving and undeserving based on skin color, wealth or both: families who had no rights that deserving families were bound to respect. She would walk with me to the city auditorium to hear The Messiah because Handel was as much our legacy as was Howlin’ Wolf. She would not submit to a narrative that would deny us access to experiences that expand the imagination or lift the human spirit. By rejecting the false narratives of the dominant culture, she claimed the right and the responsibility to turn “no way” into pathways toward dignity and possibility.

We’ll Sit at the Welcome Table

It was an every-Sunday song in my mother’s church: “We’re going to sit at the welcome table”. Having nothing else to do, I would strain my 4-year-old imagination trying to visualize such a table. Would it be covered in oil cloth like the one in my great-grandmother’s back porch kitchen? Thank goodness that I soon came to see that the welcome table is a way of living every day – not some after-death reward or a beloved kitchen table. Now my image of the welcome table includes Saturday evenings with Sammy Boy. Sammy Boy was a kid who grew up in my neighborhood. I’m not sure if he was a few years older or younger than I. I only knew that he was the only child of parents who were either “falling down or passed out drunk” by early afternoon every Saturday. I also knew that Sammy Boy had cognitive or developmental disabilities. Whether my mother had to work on weekends or not, Saturday evening suppers were always a big deal in our home. And Sammy Boy always had a place at the table. The truth was that his mother and his father were too ravaged by their own demons to properly provide (beyond the material essentials) or to protect Sammy Boy. When he took his seat at the table, he knew he was not an object of charity. In fact, if supper was delayed, he would knock at the door and ask when his supper would be ready. In later years, my mother would laugh about the time Sammy Boy looked at her as if she had lost her mind. He said, “Miss Mary, what’s wrong with you? You forgot to put my cornbread on my plate!” In other words, Sammy Boy belonged. He didn’t have to earn a seat; he had a rightful place at the family table. When his meal was over, he might hang out on the front porch or back steps and chit-chat with my mother. Then he would go home to parents who loved him the best they were able. My mother couldn’t fix them, but she could support them by caring for their son. When mother-wit informs the constellation of family, truly no child is left behind.

What is Mother-wit (or a few questions for the 21st century)

Dare I say if we had mother-wit on Pennsylvania Avenue, we would not have a 21st-century trail of tears – a pernicious policy of ripping children away from their parents?

Dare I say if we had mother-wit in the halls of Congress, there would be no policies crafted for the “deserving” at the expense of the “undeserving”?

Dare I say with mother-wit, family values would be values that uplift our shared humanity, not a political tool to benefit the “deserving, real” families?

Dare I say with mother-wit, no woman’s son would be shot in the back because of the color of his skin?

Dare I say with mother-wit, no woman’s child would have the police called on her for selling water across the street from a noisy baseball stadium?

Dare I say with mother-wit, day care and early education centers would be accessible and filled, not our innumerable prisons?

Dare I say that mother-wit would empower parents to know who is lurking behind their children’s computer screens – and what is being stockpiled in their basements?

Dare I say that mother- wit transforms the so-called immigrant crisis into a human opportunity – to engage each other in solving the very real and hard problems that we face on this planet?

With mother-wit, Mother’s Day would be a celebration of doing love – love made real, not sentimental. It would be a celebration of love that is courageous, compassionate, and expansive. It would be a celebration of family values rooted in the sure knowledge that every child is our child.

Hi Maureen,

Thank you for sharing your loving tribute to your mother and to mothers who are “doing love” every day.

Sending smiles,

Connie

Beautiful! However, I thought his name was HarryBoy! Maybe it was another person