There were some Southern traditions that my mother seemed to delight in ignoring. One was wearing roses on Mother’s Day: red if your mother was alive, white if she was deceased. I can almost imagine her wearing a dandelion in defiance of that tradition. It wasn’t that she had a fraught relationship with her mother; they were extraordinarily close and supportive of each other. It wasn’t that she didn’t like roses; her yard in summer was like a festival of blossoms: roses, dogwood, oleander, and verbena. It was more about her need to stake a claim on her personhood in a culture that denied her full humanity.

Now in this year that is the 100th anniversary of her birth, I am realizing how flowers are reminders of my mother’s real presence in my life. Perhaps that’s one of the reasons I find myself filling empty spaces with blooming things every spring. My mother had to leave school at 11 years old; her father died and as the eldest daughter, she began working as a maid to help her mother run their household. Her lack of formal education in no way diminished her desire to learn and to teach. She was the smartest sixth-grader I have ever met. Now as I watch my own grandchildren graduate from high school and prepare to enter college, I am reminded of her timeless and hard-won wisdom. I feel my mother’s presence when I notice one of the tchotchkes that my husband insisted upon bringing from her home. It is a thermometer that hung by her back door, a simple plaque inscribed with the word “Grace” and decorated with symbols of gardening. It was grace that enabled my mother Mary to shepherd me safely through the snares of American racial apartheid. It was grace, infused with a little bit of vinegar, that fortified her resolve to resist any cultural givens that compromised her choice, even if the issue at hand was as mundane as what flower to wear on Mother’s Day. Her resistance was bolstered by confidence in her own dignity and an even stronger determination to cultivate possibilities for young people in a culture specifically structured to compromise their full humanity. In African American culture, this ethos is described as “making a way out of no way”. Although I still don’t fully know how she did it, I want to share some of the lessons I have gleaned so far.

No Limits to Our Learning, No Ceiling on Our Possibilities

My cousin Peggy told me that my mother gave her an invaluable gift when she was in the first grade. Rumbling through the house as a bored six-year-old, she complained that it was too rainy to go outside and play. My mother looked at her and said, “Peggy, go and read a book. You don’t have to be in school to read.” Peggy, now Professor Emerita Peggy, said it was as if a light came on that could never be turned off. Like my mother, my cousin Peggy (aka Dr. Gloria Thurmond) is a lifelong learner and teacher. Before she became an adult, my cousin-siblings and I knew that we were obliged to learn from her.

There is another memory of a Saturday morning over sixty years ago. My mother and I were standing in front of the Rayless window, a downtown Augusta store. She asked somewhat casually, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” My seven-year-old brain searched quickly for the “upstanding” professions I knew, and I said, “A nurse.” My mother said, “That’s really nice. But you know, ladies can be doctors too.” In all truth, I had never seen a “lady doctor” of any race. However, once my mother said it, I knew it was true.

Rent = $$; Dignity – Priceless

Saturday mornings must have been the time to “get things done”. And I loved those weekends when my mother didn’t have to clean other people’s houses. One Saturday morning found us in the Lucky Real Estate office, where my mother went to pay the $30 for the shotgun house we rented on Summer Street. I can’t say for sure what cash my mother had in hand; maybe it was two twenty-dollar bills. What I do know was that the white woman whose job it was to take the payment looked at my mother and said: “Mary, you need to go and get some change.” My mother stood very still and said: “Who needs to go and get some change?” Maybe there were a few seconds of a stare down. I do know there was no ruckus; my mother appeared completely unruffled. The woman left, came back with the change, and produced a receipt. We then went on our (what was for me) merry way.

I’ve already said my mother had to leave school after sixth grade, so you know she didn’t learn negotiation in a business school. But in that potentially fraught exchange, she negotiated her obligation and established her non-negotiable dignity. She knew two things very well.

- She had to pay our rent to keep us housed.

- Any white woman who was working behind someone else’s counter on a Saturday morning (in the 1950s!) had to collect that rent.

My colleague Joyce Fletcher would describe her action as the 4 N Model of Negotiation. First, there is the naming: what is the need; what is the problem, and whose problem is it. My mother was very clear that this woman was not working behind a counter on a Saturday morning because she was seeking professional actualization. In that era of Southern culture, she was likely there because she needed a job, and that job was to collect rent money that belonged to somebody else. Then there is the norming. In a culture of “Yes, Ma’am’s” and “No, Ma’am’s”, my mother was entitled to no honorific other than her first name – no matter her age or professional status. Even if she had been a “lady doctor”, the white woman behind that counter would have called her “Mary”. And let me be clear: this woman was not being mean to my mother. According to the prevailing norms, her expectation that my mother would accommodate her convenience was completely appropriate. What she did not expect was for “Mary” to question the norm and establish herself as a co-creator of the terms of engagement. The third N of Fletcher’s model involves negotiating the actual details of a transaction. What I learned from my mother that morning was the power of stillness. She was not compelled to accommodate out of a sense of urgency. She simply stood and waited. It wasn’t too long before the woman went behind a door and came back with the proper change. Networking (the fourth N) speaks to the power of relationship. Although she walked into that office with only a skinny eight-year-old as her companion, she knew she was not alone. She was a part of a community that imbued blessed assurance of her own dignity; that she did not have to believe she was inferior just because the culture was organized to make her behave as if she were. To paraphrase the poet, Gwendolyn Brooks, she did not believe the details of inferiority just because Southern society was designed to make her live them.

Faith and Fortitude over Fear

In the poem “Legacies”, Nikki Giovanni recounts an exchange in which a girl-child resists her grandmother’s offer to teach her how to make rolls. The child knew intuitively that she needed the legacy of her grandmother’s spirit, not her ability to make rolls. When I look back in wonder about my journey from a shotgun house on Summer Street to the halls of elite academies, I know that I am carried by the legacy of my mother’s spirit. My mother practiced a soul-deep religion. It was expressed as much by her hands and her feet as by any prayer she might utter with her mouth. In fact, she shied away from people whose religiosity seemed a little too “extra”. She did not indulge in wishful thinking, nor did she wait for the rewards of a “sweet by and by”. Instead, she embraced the possibilities of now; her faith firmly rooted in the evidence of things unseen. What she passed on to me was counter-evidence, daily practices to contradict the designs of our racial apartheid culture. For example, she passed on her love of poetry, starting with Stevenson’s Child’s Garden of Verses. Although the illustrations depicted fair-haired children in faraway places and long-ago times, she taught me that there was no place my imagination couldn’t take me. As I grew older – though still in single digits- she would challenge me to memorize poems by Dunbar and Longfellow while she was away at work.

She must have had fears that troubled her soul, but she did not import them into my psyche. Here’s an example of what I mean. Although she worked for wages of $3 a day, it never occurred to me that I would not go to college. (By the way, $3 a day was the standard wage for domestic workers, who were also ineligible for Social Security benefits.) I never met her employers nor saw her place of work until I was well into my thirties. As she explained it, she was determined that neither I nor her employers would imagine me as their servant. Before catching the two buses that took her to her Murray Hill workplace, she would sometimes rise before dawn to prepare a hot breakfast and then walk the two miles with me so that I could catch the school bus taking me to a state science fair or chorus festival. When Dean Joseph Hendricks showed up at my high school to offer me a full scholarship to one of the state’s elite PWIs (actually it steadfastly remained a WI for decades), she simply exhaled and said, “Thank God”. However relieved she must have been that I received the money, I am amazed to this date that she had never communicated to me that lack of money might prevent me from going to college.

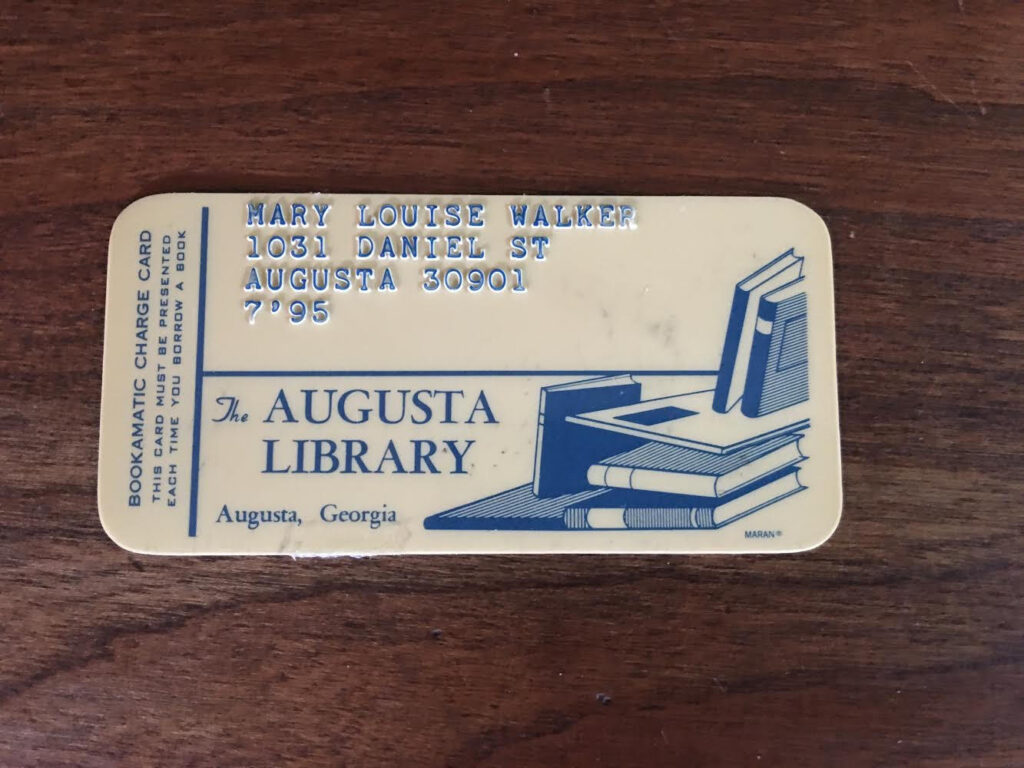

Now upon the 100th anniversary of her birth, I remember her as fearless and faith-filled. She insisted upon being the first author of her own story, resisting the dehumanizing narratives imposed by the culture. A few years before she died, she told me that her employer of over forty years called her Mary, Old Contrary whenever he thought she wasn’t listening. She got a great kick out of that.

My mother’s spirit is the lifeblood that runs through my veins. I can never share it perfectly, but it is the noblest legacy I can pass on to my children and to my grandchildren. With all my love, I say this: Hail Mary, Full of Grace, and with deepest gratitude for that little splash of vinegar.

This is absolutely beautiful. I read it and felt both inspiration and wept for the young women who are facing these troubling times given recent events targeting their rights, freedom, and justice. Thank you for honoring your readers with the story of your wonderful mother.

This is a BEAUTIFUL tribute to your mother, and to the grace and power that she displayed every day of her LIFE on Earth! THANK YOU for sharing her wisdom and grace with us!

Maureen,

You have truly caught the spirit of your mother, my second mother, beautifully. The title of your tribute, “Mary, Full of Grace, with a Little Splash of Vinegar,” summarizes the essence of her beauty, dignity, wisdom and overall extraordinary life. She was a gift to our family and to all who were blessed to really know her.

An amazingly strong, intelligent, graced-filled woman who raised an amazingly strong, intelligent, and grace-filled daughter. Happy Birthday Miss Mary Walker. May your memory always be a blessing.

Maureen,

This is truly an appropriate title for your tribute to your mother, and my second mother. She was a beautiful gift from God who lived her life with dignity, love, wisdom, generosity, faith and fortitude. She was an awesome blessing to her family, whose influence will be felt for generations to come. Happy 100th Birthday, Auntie!

Maureen, your mom was a hot ticket!

Love this line: “My mother’s spirit is the lifeblood that runs through my veins.”

I totally see you in the description of her.

It would be the greatest honor to me to have my kids say that one day about me.

Happy 100th Birthday “Mary Full of Grace with a Little Splash of Vinegar.” I remember you with love. ❤️

I cannot adequately describe the joy and delight I got reading this! Your mother embodied, the song,“ May the life I lead speak for me” What a life and thanks for all the ways you shared she informed and shaped your life- who you are. Happy 100th anniversary of her birth! You are the spitting image of your beautiful mom!

What a beautiful life — may you always embody the spirit of Mary, Full of Grace, with a Little Splash of Vinegar.

I loved reading this ❤️

Thank you , I am shy about writing on public platforms but I was inspired by your story .

Thank you for the way your words both pay tribute to your mother while weaving a very powerful story from recounting a moment in time. How she and women like her, made what we consider ordinary, extraordinary. I thank you and I thank her.