In gratitude and memoriam for Erica Garner, Heather Heyer, Fannie Lou Hamer, Coretta Scott King, Dorothy Parker, Ida B. Wells, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg

I know. I can hear the indignant objections now. Somehow in the past two years, what was a “comical” media meme is now loaded with racialized invective, evoking everything from oblivious entitlement to rancid ideologies (implicit or explicit) to culturally sanctioned violence. Believe me: I know how it feels to be “known” and regulated by terms made up by someone else. I get how offensive and unfair such a meme must feel. But bear with me. I think it’s well past time to stop skirting the issues. We might still laugh at the SNL Black Jeopardy skits, but we also need to examine some sobering realities.

Karen kar⋅ren\ ker’ren\noun, adj., (2017/2018); plural Karens: 1: possesses an ingrained sense of superiority, maybe conscious or not; 2: manifests in behavior that presumes entitlement to safety, security, and deference; empowerment to monitor, judge, and report . . . .

How is it that in 2020 “Karen” behavior is so prominently in our cultural landscape? Is it new? Is there a cultural DNA shared across generations from Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Carolyn Bryant to Amy Cooper? These questions are as old as our nation – actually older. Even as our founders were struggling with notions of freedom and independence, they were crafting practices of power to determine who could be free, in what measure, and once gained, the uses to which such freedoms might be put. Constructions of race, gender, and class proved handy, functioning then as they do now as regulators of belonging and mattering. Then as now, white women have played a role in this process: sometimes to upend patriarchal power structures, sometimes using the power of adjacency to collude with racialized terrorism, and more often than we might like to believe, doing both at the same time. The “both-and” role of white women raises nettlesome questions. They are questions that prick consciences; they are also questions that offend and enrage. Sometimes they make all of us, irrespective of racial identities scuttle away into the illusory comforts of anger or niceness. However, if we have the courage to walk together with these questions, we might find ourselves on the precipice of hope and new possibilities.

Maybe I should just tell about the three incidents that compelled me to write this blog. A few weeks ago, as I was passing through my family room, I heard the commentator Dana Bash say something about electoral politics and “suburban” women. I didn’t stay to figure out what she meant, but I got the impression that she wasn’t talking about me. No big deal: the generic term “women” rarely fits my experience. I had recently read Paul Krugman’s trenchant analysis of this current president’s “racist, statist suburban lifestyle dream”. Though with somewhat dissimilar rhetorical purposes, both Bash and Krugman were shining a light on the president’s pandering to “suburban women” and their need to “feel safe”. Even though I have lived in “suburbs” all of my adult life, I was pretty clear that any pandering that was happening was not directed to me. Then there was a much more personal incident from early January 2020 – when it was still possible to walk unmasked into a neighborhood bookstore. I was following up on publicity information I had sent to the store about my recently published book. Having lived in that neighborhood for eighteen years and being the bibliophile (or addict) that I am, I can honestly say that I had bought hundreds of books in that store. Furthermore, the bookstore is in a college town, and I had often seen sidewalk boards marketing author talks and touting local authors. What better place to offer to do a local author book talk and a signing? At least that’s what I thought until I spoke with a store manager. The first argument was economic; so, I told her about the guarantees my publisher was offering to ensure against any loss. Next, she said my book was “old”; it was January already and my book was published in late November. Then came the coup de grace: She explained that her customers were “suburban women” who liked literature and cookbooks.  She went to advise me to try to sell my idea in an “urban” market. All of this was said in language that I can only describe as “steely politese”. Having done her job, she pushed back from the table and began to walk away. I was nonplussed. I did muster enough presence of mind to inform her that I understood her neighborhood having lived there for several years, having had a child who was educated there for 8 years, and having strong professional ties with the local college for many years. I wished I had remembered to tell her that as a suburban woman who had frequented that store for 20 years, I had never bought a cookbook. As a writer, I know all about rejection. However, I have to confess I had never experienced one that cut quite so deeply.

She went to advise me to try to sell my idea in an “urban” market. All of this was said in language that I can only describe as “steely politese”. Having done her job, she pushed back from the table and began to walk away. I was nonplussed. I did muster enough presence of mind to inform her that I understood her neighborhood having lived there for several years, having had a child who was educated there for 8 years, and having strong professional ties with the local college for many years. I wished I had remembered to tell her that as a suburban woman who had frequented that store for 20 years, I had never bought a cookbook. As a writer, I know all about rejection. However, I have to confess I had never experienced one that cut quite so deeply.

It was tempting to numb the sting of this encounter by dismissing this woman as a “Karen”. That she would glibly invoke the sensibilities of “suburban women” to discount my offer was indicative of something more sinister that is happening in this nation. A culture in which words have no anchoring meaning is devolving toward moral collapse. The president and his toadies would have us believe there are no truths; there is no right and wrong. Neo-Nazis and gun-toting liberators who invade houses of government are all “fine people”. Brown children incarcerated in cages don’t need their parents, medicine, or soap. Rich men can assault women (and girls) with impunity; it’s okay to “move heavily” on them and wish their pimps good luck. Worst of all, we are being goaded into believing that we do not know what we know. So, let’s be clear: when the president and his enablers (in the White House, the non-Rose Garden, the media, evangelical pulpits, wherever) talk about “suburban women”, they are not talking about geography. They are not even talking about socio-economics. They do not care if you live in a stately mansion behind a manicured lawn or in a trailer on a rutted dirt road. They are appealing to one aspect of intersectional identity: whiteness. The descriptor “suburban women” is not a demographic appeal; it is a summons to action.

U(ncle) S(am) Wants You!

Actually, it is probably more appropriate to say, “needs you”. That’s how the white supremacist, patriarchal hierarchies work in the United States: by conscripting white women as well as black/indigenous people of color (BIPOC) into service. (How else does one explain a Daniel Cameron and Candace Owens? But that’s another blog.) Once pressed into service, their primary job is to give the purposes and practices of systemic racism a veneer of credibility. As convenient as it may be to attribute the violence of racial injustice to “straight white men”, they really can’t do it all by themselves. They need “helpers” to keep the system operational – to make racial injustice look likewise and necessary public policy. Hence, the call to “suburban women” is laced through with rhetoric about safety and security. The call also carries an embedded promise (however illusory) of caring protection: “These policies and practices (however violent and unconstitutional) are necessary to ensure your well-being – and most important – your status in the racial hierarchy”. Although the quotation marks are a bit of an improvisation, the message comes through loud and clear – whether by dog-whistle or bullhorn.  In order to protect their precarious position in the gender hierarchy, “suburban women” are recruited to be the face of systemic racism, intimate, interpersonal, and institutional. Because of their adjacency to the white patriarchal power structure, white women have always had a second-class seat. A “second class seat” can always be exploited: people occupying those seats can be readily deployed against anyone who threatens to encroach upon their already precarious positions in the power hierarchy.

In order to protect their precarious position in the gender hierarchy, “suburban women” are recruited to be the face of systemic racism, intimate, interpersonal, and institutional. Because of their adjacency to the white patriarchal power structure, white women have always had a second-class seat. A “second class seat” can always be exploited: people occupying those seats can be readily deployed against anyone who threatens to encroach upon their already precarious positions in the power hierarchy.

Given all that women of all colors and cultures do to foster healing, it is difficult to talk about the deep-structured racial divide between women in the United States. It is difficult because most of us have the experience of forming deep and abiding sisterhood relationships – in spite of institutional and cultural barriers. Even as I write this sentence, I am feeling the presence of Sonja, a white woman whose love for me brought her to my hospital bed at midnight. Hers was the first face I saw upon waking from major surgery. Seeing my confusion (and gratitude!), she simply said: “Where else can I be”. There was a practical answer to that question: she could have been at her own home, with her husband, twenty miles away. Perhaps these experiences of knowing, loving, and working together provide the most compelling reason for us to deconstruct the racialized patriarchal contract that functions to divide us. We must name and denounce the derivative powers bestowed upon white womanhood through adjacency to white men: power that can also be used to oppress Black Indigenous people of color, irrespective of gender identification.

Our histories provide ample examples of how these divisions work. Even though Elizabeth Cady Stanton considered herself an abolitionist and worked closely with Frederick Douglass to secure women’s suffrage, she never relinquished her claim on white racial supremacy. In her words: ‘We educated, virtuous white women, are more worthy of the vote.’ On other occasions, she went on to speculate about the suffering that white women and their daughters would experience if “degraded black men were allowed to have the rights that would make them even worse than their Saxon fathers”. It might be a fair statement to say that was then; she was a woman of her time. But this anti-black racism didn’t stop then, did it? How is it that white women from then until now feel empowered to police or otherwise regulate black bodies, whether they are picnicking, buying a taco, napping in a dormitory lounge, or simply trying to go home? How else might we explain the St. Louis woman – an attorney – who stood with her husband and pointed a gun at racial justice protesters who were marching past their home? How do we explain the mother who drove her teenaged son and his assault rifle from his home in Illinois to Kenosha, Wisconsin, where he would kill two people? When I see photos of smiling white families at Sunday lynching picnics, I’m pretty sure it was the “straight white men” who tied the nooses and hoisted the black bodies up to the limbs of the tree. I am also pretty sure they did not dress the children or make the potato salad and apple pies for the picnic. Now in the 21st century, we have the viral videos of Karens Gone Wild. Let me be extra clear here: I know these women do not represent all white women. What I also know is that they represent extreme enactments of a racialized, patriarchal contract that is actionable by all white women. To use Hillary Clinton’s verbiage, extreme enactments make racism look “deplorable”. More moderate enactments make racism look adaptive. Systemic anti-black racism has nothing to do with having black friends, colleagues, family members, or lovers. In these United States, racialized, patriarchal power structures need the face of white womanhood to make systemic racism work. And here’s how it looks and sounds when systemic racism is working.

“But you are a formidable presence!”

When I heard those words, I knew I wasn’t being complimented. I knew that “formidable” meant unapproachable, somehow a bit scary. I also wanted to laugh when I thought about all of my BIPOC friends, relatives, students, and colleagues – none of whom had ever described me as formidable. But one does not laugh in the middle of an interrogation by a white dean who wanted to know why I had not consented to change a white female student’s grade from an A- to an A. The student (whom he described as one of the best in the graduate program) had complained that my standards were too exacting and that she felt intimidated when I asked her to offer her reasoning or provide some evidentiary support for her frequent in-class comments. Although the dean said that my explanation was credible, he directed me to change the grade. This anecdote is not offered as a “woe is me” tale; I in no way feel isolated in this experience. Any BIPOC academic can offer similar stories (plural)! What happened in this scenario is exactly what Amy Cooper thought would happen when she said she felt affronted by an African American man. This young white female knew that she could cancel any notions I might have about academic integrity by appealing to her white dean. Racial adjacency provided a protective layer of entitlement to academic comfort.

Here’s the point. The call to “suburban women” extends beyond a right to physical safety; it also includes professional validation and emotional comfort. As Sheri Parks recounts in her book Fierce Angels, a white father of a first-year college student expressed relief when he saw that she was an academic dean. He reassured his daughter that she would be fine because “a black woman would be taking care of her”.  The promise of safety begs the question: safe from what or from whom? If there is a need for safety, there must be looming danger, some threat to the social order. Enter the Angry Black Woman and the Angry Black Man. The consequences of these stereotypes can be lethal – as in dead on the sidewalk lethal. Amber Guyger’s and Patricia McCloskey’s notwithstanding, most white women will never squeeze the breath out of someone or shoot someone in the back seven times. But as one cyber-pundit put it, if this kind of racism can happen in public, imagine what can happen in the privacy of a human resources office, or a boardroom, or a classroom. What can happen is intense scrutiny: the demand for black women to be consistently accommodating, the demand for black men to be relentlessly jovial. To violate that implicit contract between white women and the patriarchy can land any BIPOC employee, student, or friend in a danger zone.

The promise of safety begs the question: safe from what or from whom? If there is a need for safety, there must be looming danger, some threat to the social order. Enter the Angry Black Woman and the Angry Black Man. The consequences of these stereotypes can be lethal – as in dead on the sidewalk lethal. Amber Guyger’s and Patricia McCloskey’s notwithstanding, most white women will never squeeze the breath out of someone or shoot someone in the back seven times. But as one cyber-pundit put it, if this kind of racism can happen in public, imagine what can happen in the privacy of a human resources office, or a boardroom, or a classroom. What can happen is intense scrutiny: the demand for black women to be consistently accommodating, the demand for black men to be relentlessly jovial. To violate that implicit contract between white women and the patriarchy can land any BIPOC employee, student, or friend in a danger zone. An African American client of mine found herself in the danger zone when her manager reprimanded her in a directors’ meeting for “rolling her eyes”. As the only person of color in a room with fifteen of her white colleagues, she felt humiliated. She was also stunned because this manager identified as socially progressive and made a point of cultivating non-hierarchical relationships with her direct reports. Of course, her manager couldn’t have known that an errant hair had fallen into my client’s eye; however, she didn’t have to assume that blinking eyelids meant that her comments (and her authority) were being challenged. In literally the blink of an eye, my client was transformed from a collaborative (and pliant?) colleague into an Angry (or Uppity) Black Woman. Anyone who has ever worked in an institution knows that the “not a team player” or the “doesn’t fit in” narrative sounds the death knell to one’s career. That is likely why a young black male consultant assured a group of senior management white women that he was “the kind of brother who could be happy anywhere”. He was on a phone conference and assumed that as was usually the case, he was talking to all white women. As an up-and-coming African American male who was trying to keep his consulting gig, his first order of business was to assure white females that they were “safe” with him.

An African American client of mine found herself in the danger zone when her manager reprimanded her in a directors’ meeting for “rolling her eyes”. As the only person of color in a room with fifteen of her white colleagues, she felt humiliated. She was also stunned because this manager identified as socially progressive and made a point of cultivating non-hierarchical relationships with her direct reports. Of course, her manager couldn’t have known that an errant hair had fallen into my client’s eye; however, she didn’t have to assume that blinking eyelids meant that her comments (and her authority) were being challenged. In literally the blink of an eye, my client was transformed from a collaborative (and pliant?) colleague into an Angry (or Uppity) Black Woman. Anyone who has ever worked in an institution knows that the “not a team player” or the “doesn’t fit in” narrative sounds the death knell to one’s career. That is likely why a young black male consultant assured a group of senior management white women that he was “the kind of brother who could be happy anywhere”. He was on a phone conference and assumed that as was usually the case, he was talking to all white women. As an up-and-coming African American male who was trying to keep his consulting gig, his first order of business was to assure white females that they were “safe” with him.

“Formidable” Epilogue

I changed the grade as directed. The change of grade form required that I list a reason for the change, and I did: “At the direction of the dean”. I immediately received a phone call telling me I was not allowed to say that. When I explained that I had no other reason that I could submit, the conversation ended. I would bet that if anyone were to see that form today, the explanation that I gave will have been whited-out (pun intended).

“For she may turn out to be the queen of femininity”

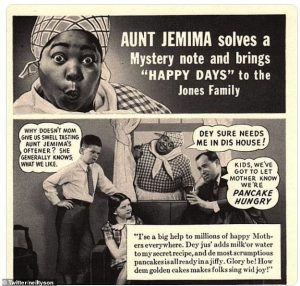

One of the more toxic messages of patriarchal culture is that a woman’s physical appearance determines her worth. It follows then that this culture would define the markers of beauty; we all know what they are – fair skin, non-curly-coily hair, small stature.  The extent to which a woman possesses these markers determines her femininity – her desirability, the degree to which she matters in a patriarchal culture. Beauty, therefore, is constructed as a property of whiteness. It is characteristic of a racialized patriarchy to deploy a tactic that demeans all women to amplify divisions between white and Black/ Indigenous women. With physical appearance as a marker of worth, “better than “or superior status is promised to white women. It is, however, a precarious status, one that needs tending and safeguarding if it is to function as a racial differentiator. Implicit in this “better than” status is entitlement to deference and subservience. In other words, physical appearance plays a significant role in the politics of racial stratification among women. It is no accident that early images of “Aunt Jemima” featured a large-sized woman with charcoal-black skin on a shiny, smiling face. Hollywood has definitely proliferated the Mammy stereotype, from Hattie McDaniel to the very talented Octavia Spencer. Across generations, the likeability of black women is based on their serviceability to women who look nothing like them. Think that’s a trope from a bygone era? Hmm… maybe. But I can’t help but think of the character Mo, a large-sized, dark-skinned, gender-fluid aspiring DJ who plays confidante-sidekick to the white-skinned, small-sized, sometimes hapless, and hopelessly heterosexual Zoe. The optics could not be starker and are hardly accidental. Mo occasionally offers up some finger-snapping advice, kind of a 21st-century form of caretaking. However, relationships marked by intimacy without parity are in fact rather cliché and consistent with the cultural role of the subservient “Magical Negro”.

The extent to which a woman possesses these markers determines her femininity – her desirability, the degree to which she matters in a patriarchal culture. Beauty, therefore, is constructed as a property of whiteness. It is characteristic of a racialized patriarchy to deploy a tactic that demeans all women to amplify divisions between white and Black/ Indigenous women. With physical appearance as a marker of worth, “better than “or superior status is promised to white women. It is, however, a precarious status, one that needs tending and safeguarding if it is to function as a racial differentiator. Implicit in this “better than” status is entitlement to deference and subservience. In other words, physical appearance plays a significant role in the politics of racial stratification among women. It is no accident that early images of “Aunt Jemima” featured a large-sized woman with charcoal-black skin on a shiny, smiling face. Hollywood has definitely proliferated the Mammy stereotype, from Hattie McDaniel to the very talented Octavia Spencer. Across generations, the likeability of black women is based on their serviceability to women who look nothing like them. Think that’s a trope from a bygone era? Hmm… maybe. But I can’t help but think of the character Mo, a large-sized, dark-skinned, gender-fluid aspiring DJ who plays confidante-sidekick to the white-skinned, small-sized, sometimes hapless, and hopelessly heterosexual Zoe. The optics could not be starker and are hardly accidental. Mo occasionally offers up some finger-snapping advice, kind of a 21st-century form of caretaking. However, relationships marked by intimacy without parity are in fact rather cliché and consistent with the cultural role of the subservient “Magical Negro”.

So, who can be Miss America, the queen of femininity? Well, according to Rule Seven that was in place until 1970, only women who were “of good health and of the white race”. The existence of this rule seems somewhat superfluous given the fact that the racial politics of the pageant were always on blatant display. For example, in the earliest days of the pageant, Black Atlantic City residents costumed as slaves were hired to escort the participants to the opening ceremonies. The intersection of gender and racial politics could not be more obvious. Isn’t it interesting that the first pageant took place about a year after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment? (There goes that racialized patriarchy again!) Thank goodness, the cultural landscape has shifted. It is hardly the case that a “million girls more than pretty” aspire to make their “dreams come true in Atlantic City”. Nevertheless . . .

“There, she is

Fairest of the fair, she is… Miss America!”

The precipice of despair can become a portal to possibilities.

Talk about intersectionality! The patriarchal set-up promotes and profits from racialized divisions among women. We can hardly be surprised that it functions to goad women into scrambling for a “second class seat” (as one of my students put it), sometimes by any means necessary. This inherited power set-up makes white women susceptible to growth-stunting behaviors such as denial, repression, and projection, thus cleansing themselves of their fears, anger, and shame. It demeans and subjugates black and indigenous women (which breeds its own set of growth-stunting problems, but that too is another blog). The current occupant of the White House didn’t invent this mess, but he is all too happy to exploit it to seize and consolidate power. Not surprisingly, his strategy is straight out of any generic fascist playbook: appeals to exceptional birthright, motherhood, sexual attractiveness, independence, ferocity, and (paradoxically) fragility. His campaign for power depends for effect upon fear-mongering: images of hulking black figures breaking into the homes of elderly white women, white women assaulted by black men in subways, and horror of horrors, a “suburban” woman learning that “Antifa is moving in next door”. He delights in whipping up his base which includes White Nationalist Women into a frenzy. As one self-dubbed Angry White Woman blogger put it: “We refuse to act like one of the conquered races and learn other people’s languages.” What makes them dangerous is that their outrageous rhetoric is subjected to refinement, thereby making it palatable for widespread consumption and reproduction. Nikki Haley, I submit, represents white nationalism in a very expensive dress. Although she references her sari-wearing mother to establish herself as a person of color, she also identifies as white on her voter registration. While she cites the hardship and discrimination experienced by her turban-wearing father, she blames people for “giving in” to discrimination and hatred. Racism in America, according to Nikki, is “a lie”. I suppose in Nikki-world, experiencing racism makes you either a liar, a weakling, or part of the problem. As this refined vitriol insinuates itself into the broader culture, reports of verbal and nonverbal hostilities among women in shopping malls, parking lots, and virtual office cubicles proliferate. Who would have ever guessed that in this COVID-era, masks would become such divisive political weapons? Once outrageous racist rhetoric is refined, it may seem reasonable, justifiable, innocent, or morally neutral. Sufficiently distanced from White Nationalist Women, “Karen” behavior is liberated to do the work of everyday racism.

This current era requires us to face hard truths about this patriarchal power structure that promotes and profits from racialized divisions among women, irrespective of ethnicities, sexualities, and economic privilege. We must do this because as malevolent as the current occupant of the White House is, he didn’t start any of this; he’s just agitating latent tensions to push us into despair. He and the patriarchal powers for which he is a proxy would have us give up on healing, resisting, and repairing the breach that has limited our re-imagining of more authentic (i.e. stronger, more sustainable, spiritually satisfying) sisterhoods.

We do try some workarounds, but if this present political season is telling us anything, it’s that the workarounds are not enough. For example, we do niceness very well. We can be and often are very solicitous toward each other. Niceness is all well and good unless it is actually a way of just getting along and getting past each other. Niceness can never cancel the normalization of systemic racism. Sometimes we perform niceness to serve our own preferred narrative or simply to avoid having to “really deal” with ourselves and each other. How do we know when we’re into our “nice narrative”? Notice how quickly we give it up. What does the “other” woman have to do or say – or not do or say – to justify our decision that she no longer deserves our beneficence?

How might we open the portals to possibilities? Here are four things we can do, as well as a few things we can stop doing. First, let’s start with the simple but hard stuff – like eye contact. How often do we become studiedly preoccupied to avoid looking at each other warmly- face to face, eyes to eyes? (Come on. I know I’m not the only one.) It’s a risk I know: warm eye contact might be met with an icy glare. On the other hand, if we can set aside our egoic entitlement to immediate gratification, we might experience the joy of co-creating a positive relational moment – one in which we literally (if only temporarily) change each other’s brains.

Second, let’s expand what we mean by systemic racism. We all get it: systemic racism is encoded in the laws, public policies, and business practices that result in the physical and political death of BIPOC citizens of any gender. But here’s the thing: systemic racism does not depend for its effectiveness upon legislative edict. It is reinforced, encounter by encounter, meeting by meeting. It is way too easy to off-load blame for systemic racism onto white men who have “all the power”. We all have power of some sort, and white women have the power of adjacency.

If you don’t believe adjacency matters, look at the affirmative action stats. Better yet, look at who occupies the “comfort class seats” in your organization.

Here’s an example of how you might use the power of adjacency. If you know that your organization “accelerates” the careers of non-minoritized employees through formal or (more likely) informal practices, pummel the wall of exclusion with justice questions. It’s not enough to ask how we make our organization more inclusive. Also ask, “What are we doing right now to create exclusion? It is not enough to ask what we have to do to “let them in” – a question which problematizes “them” from the outset. Also ask, “What are we doing right now to keep them out? Which of our practices have the impact – even without the intention – of hobbling the careers of BIPOC employees”? For good measure, also take note of bodies that are included in the pronouns “we” and “our”. Whomever you see is a telling indicator of who really belongs.

Want to call out exceptions to the rule? Great! That would be a third transformative action, especially if we look to exceptions for encouragement – not for disproof of our painful realities. White women have a strong and steady history of anti-racism; it is also a history that has been largely suppressed. It is now time to look for the “invisible revolutionaries”– women who used their powers to participate in justice-making. Names like Anne Braden, Karen Branan, and Lillian Smith come to mind, women who rebuked the racial mores and moralities of their time. These are women who chose to unlearn the cultural education that required them to “split their bodies from their minds and both from their souls”. In her book Killers of the Dream, Smith recalled the mother who taught her what she knew of “tenderness and love”, but also “the bleak rituals of keeping Negros in their place”. That kind of split morality is not from days long ago. In fact, it is in the breach between professed values and preferred realities that adaptive racism thrives. The irony is that nice, non-nationalist white women are more prone to enact it. Women who revere the racialized patriarchy (no matter how sordid and sullied the actual patriarch is) are happy to be the Karen’s of our world.

The really good news about justice-making is that we never have to do it alone; neither do we have to do it perfectly. In fact, we can’t do it alone and we can’t do it perfectly. We are reminded by AOC that no one needs to “die on a hill” to stand for justice. Justice can be served by an awkward conversation across a neighborhood fence. Neither is principled commitment sustained by grandiose heroics. Individual heroism is just one of the stultifying myths of American exceptionalism. It works to thwart mutual empowerment. Justice is served when we help someone who is a little more vulnerable, someone who has a little less access to material and relational resources than we do – resources that translate into empowerment.

Authentic sisterhood is anti-racism that requires us to develop this kind of disruptive, and ultimately liberatory, empathy. It enables us to stand together as we evolve toward a larger imagination of who we can be. It enables us to walk together however falteringly to free ourselves from the tropes – Karen, Becky, Jemima, Sapphire, – that perpetuate the aims of a racist patriarchal culture. Until we move toward larger possibilities, we will “dance the dance that cripples the human spirit, step by step by step” and fall inevitably into a pit of fear and despair. Perfection is not required to open portals to possibilities. That’s a good thing because not one of us is perfect. We don’t have to spend our days performing “wokeness” – brashly calling each other out. What we can and must do is to call each other in, imperfectly and lovingly.

We might do well to embrace these words from Maria Popova:

“To be human is to leap toward our highest moral potentialities, only to trip over the foibled actualities of our reflexive patterns. To be a good human is to keep leaping anyway”.

In spirit and in truths,

Maureen

Thanks so much for this Maureen. I too have had a questioning reaction to the tern “suburban women” —what is that code for? I also have a reaction to the word “folks” which is never used to describe a group of powerful, rich, white people. You give me the inspiration and courage to keep tripping and keep trying as I strive to contribute to the vision of who we can be.

Whoa, Maureen…as so many times in the past your authenticity and courage to speak from a place of knowing and living it causes me once again to pause and try to take in with mind, heart and soul.

There’s so much, I need to simply read again and try to notice where are points I stayed in connection and times where the tension was connected to my choice to turn away vs toward.

I appreciate the invitation to stay awake and will share this with others trying to do the same….,, well not just awake but stepping into concrete action that is in service of change.

much love

Patricia Moore

I just discovered this excellent essay and it/you made my day, week, year, possibly decade by putting me in a sentence with my heroes — Lillian Smith & Anne Braden. It’s not easy being Karen but plaudits like this sure help! Thank you, Maureen.